David was a tech reviewer for the book and these two excellent articles on inversion of control are cross-posted from his blog where you can find lots more excellent content.

When I first learned to program, the code I wrote all followed a particular pattern: I wrote instructions to the computer that it would execute, one by one. If I wanted to make use of utilities written elsewhere, such as in a third party library, I would call those utilities directly from my code. Code like this could be described as employing the ‘traditional flow of control’. Perhaps it’s just my bias, but this still seems to me to be the obvious way to program.

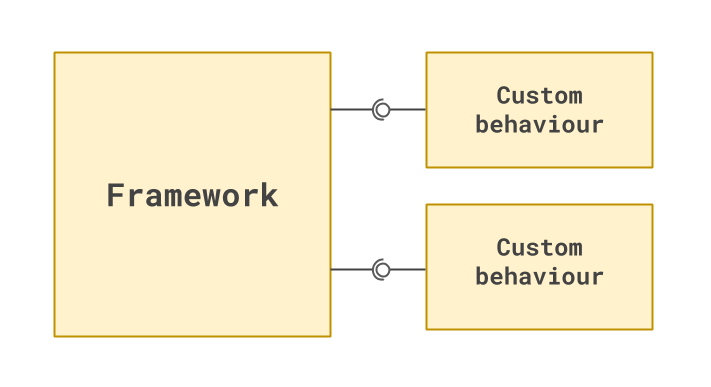

Despite this, there is a wider context that the majority of the code I write today runs in; a context where control is being inverted. This is because I’m usually using some kind of framework, which is passing control to my code, despite having no direct dependency on it. Rather than my code calling the more generic code, the framework allows me to plug in custom behaviour. Systems designed like this are using what is known as Inversion of Control (IoC for short).

This situation can be depicted like so: the generic framework providing points where the custom code can insert its behaviour.

Even though many of us are familiar with coding in the context of such a framework, we tend to be reticent to apply the same ideas in the software that we design. Indeed, it may seem a bizarre or even impossible thing to do. It is certainly not the ‘obvious’ way to program.

But IoC need not be limited to frameworks — on the contrary, it is a particularly useful tool in a programmer’s belt. For more complex systems, it’s one of the best ways to avoid our code getting into a mess. Let me tell you why.

Striving for modularity

Software gets complicated easily. Every programmer has experienced tangled, difficult-to-work with code. Here’s a diagram of such a system:

Perhaps not such a helpful diagram, but some systems can feel like this to work with: a forbidding mass of code that feels impossible to wrap one’s head around.

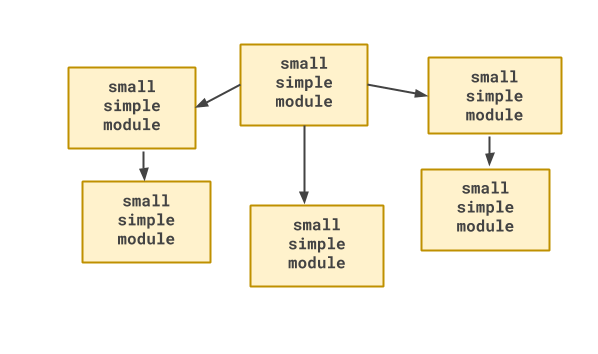

A common approach to tackling such complexity is to break up the system into smaller, more manageable parts. By separating it into simpler subsystems, the aim is to reduce complexity and allow us to think more clearly about each one in turn.

We call this quality of a system its modularity, and we can refer to these subsystems as modules.

Separation of concerns

Most of us recognise the value of modularity, and put effort into organising our code into smaller parts. We have to decide what goes into which part, and the way we do this is by the separation of concerns.

This separation can take different forms. We might organize things by feature area (the authentication system, the shopping cart, the blog) or by level of detail (the user interface, the business logic, the database), or both.

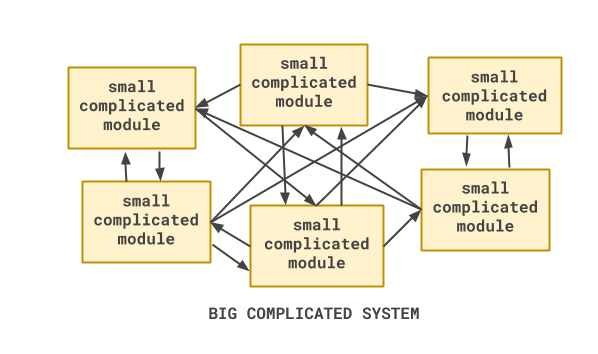

When we do this, we tend to be aiming at modularity. Except for some reason, the system remains complicated. In practice, working on one module needs to ask questions of another part of the system, which calls another, which calls back to the original one. Soon our heads hurt and we need to have a lie down. What’s going wrong?

Separation of concerns is not enough

The sad fact is, if the only organizing factor of code is separation of concerns, a system will not be modular after all. Instead, separate parts will tangle together.

Pretty quickly, our efforts to organise what goes into each module are undermined by the relationships between those modules.

This is naturally what happens to software if you don’t think about relationships. This is because in the real world things are a messy, interconnected web. As we build functionality, we realise that one module needs to know about another. Later on, that other module needs to know about the first. Soon, everything knows about everything else.

The problem with software like this is that, because of the web of relationships, it is not a collection of smaller subsystems. Instead, it is a single, large system - and large systems tend to be more complicated than smaller ones.

Improving modularity through decoupling

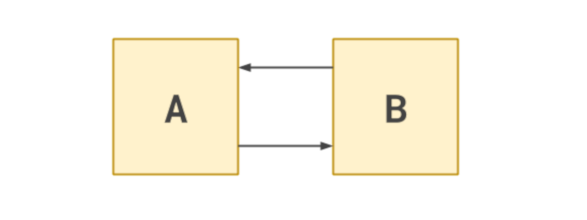

The crucial problem here is that the modules, while appearing separate, are tightly coupled by their dependencies upon one other. Let’s take two modules as an example:

In this diagram we see that A depends on B, but B also depends upon A. It’s a

circular dependency. As a result, these two modules are in fact no less complicated than a single module.

How can we improve things?

Removing cycles by inverting control

There are a few ways to tackle a circular dependency. You may be able to extract a shared dependency into a separate module, that the other two modules depend on. You may be able to create an extra module that coordinates the two modules, instead of them calling each other. Or you can use inversion of control.

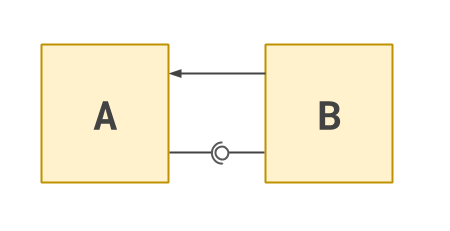

At the moment, each module calls each other. We can pick one of the calls (let’s say A’s call to B) and invert

control so that A no longer needs to know anything about B. Instead, it exposes a way of plugging into its

behaviour, that B can then exploit. This can be diagrammed like so:

Now that A has no specific knowledge of B, we think about A in isolation. We’ve just reduced our mental overhead,

and made the system more modular.

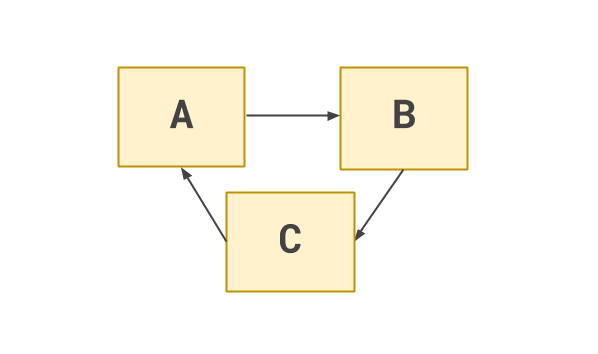

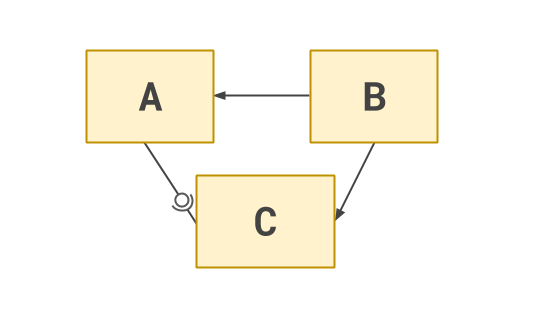

The tactic remains useful for larger groups of modules. For example, three modules may depend upon each other, in a cycle:

In this case, we can invert one of the dependencies, gaining us a single direction of flow:

Again, inversion of control has come to the rescue.

Inversion of control in practice

In practice, inverting control can sometimes feel impossible. Surely, if a module needs to call another, there is no way to reverse this merely by refactoring? But I have good news. You should always be able to avoid circular dependencies through some form of inversion (if you think you’ve found an example where it isn’t, please tell me). It’s not always the most obvious way to write code, but it can make your code base significantly easier to work with.

There are several different techniques for how you do this. One such technique that is often talked about is dependency injection. I will cover some of these techniques in part two of this series.

There is also more to be said about how to apply this approach across the wider code base: if the system consists of more than a handful of files, where do we start? Again, I’ll cover this later in the series.

Conclusion: complex is better than complicated

If you want to avoid your code getting into a mess, it’s not enough merely to separate concerns. You must control the relationships between those concerns. In order to gain the benefits of a more modular system, you will sometimes need to use inversion of control to make control flow in the opposite direction to what comes naturally.

The Zen of Python states:

Simple is better than complex.

But also that

Complex is better than complicated.

I think of inversion of control as an example of choosing the complex over the complicated. If we don’t use it when it’s needed, our efforts to create a simple system will tangle into complications. Inverting dependencies allows us, at the cost of a small amount of complexity, to make our systems less complicated.

Further information

- Part two of this series: Three Techniques for Inverting Control, in Python.