David was a tech reviewer for the book and these two excellent articles on inversion of control are cross-posted from his blog where you can find lots more excellent content.

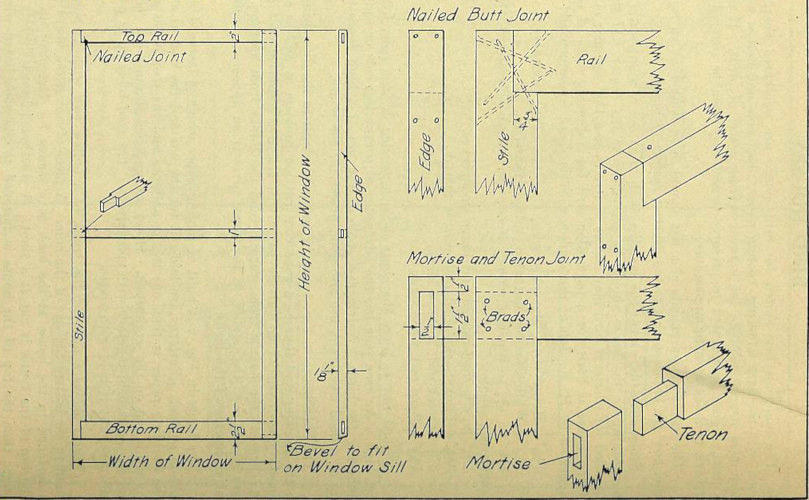

In the previous post we learned how Inversion of Control can be visualised as follows:

B plugs into A. A provides a mechanism for B to do this — but otherwise A need know nothing about B.

The diagram provides a high level view of the mechanism, but how is this actually implemented?

A pattern for inverting control

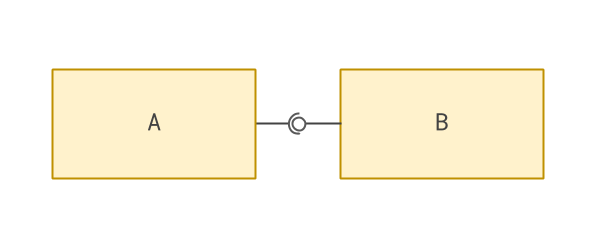

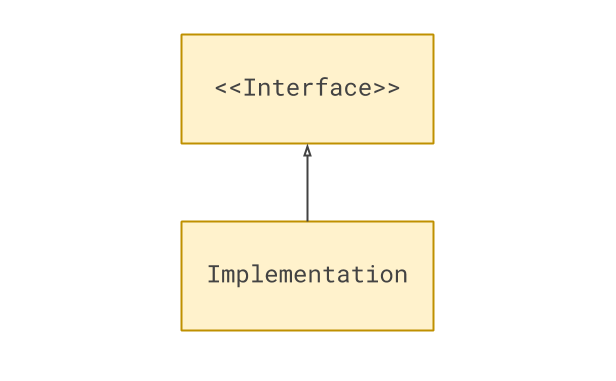

Getting a little closer to the code structure, we can use this powerful pattern:

This is the basic shape of inversion of control. Captured within the notation, which may or may not be familiar to you, are the concepts of abstraction, implementation and interface. These concepts are all important to understanding the techniques we’ll be employing. Let’s make sure we understand what they mean when applied to Python.

Abstractions, implementations and interfaces — in Python

Consider three Python classes:

class Animal:

def speak(self):

raise NotImplementedError

class Cat(Animal):

def speak(self):

print("Meow.")

class Dog(Animal):

def speak(self):

print("Woof.")

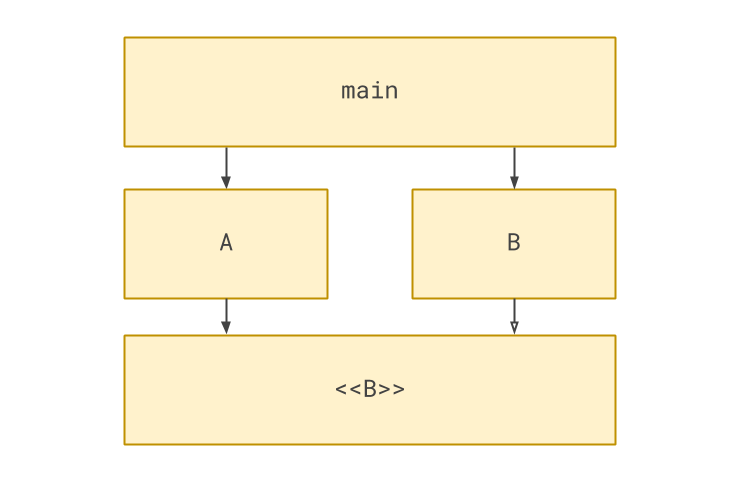

In this example, Animal is an abstraction: it declares its speak method, but it’s not intended to be run (as

is signalled by the NotImplementedError).

Cat and Dog, however, are implementations: they both implement the speak method, each in their own way.

The speak method can be thought of as an interface: a common way in which other code may interact with

these classes.

This relationship of classes is often drawn like this, with an open arrow indicating that Cat and Dog are concrete

implementations of Animal.

Polymorphism and duck typing

Because Cat and Dog implement a shared interface, we can interact with either class without knowing which one it is:

def make_animal_speak(animal):

animal.speak()

make_animal_speak(Cat())

make_animal_speak(Dog())

The make_animal_speak function need not know anything about cats or dogs; all it has to know is how to interact

with the abstract concept of an animal. Interacting with objects without knowing

their specific type, only their interface, is known as ‘polymorphism’.

Of course, in Python we don’t actually need the base class:

class Cat:

def speak(self):

print("Meow.")

class Dog:

def speak(self):

print("Woof.")

Even if Cat and Dog don’t inherit Animal, they can still be passed to make_animal_speak and things

will work just fine. This informal ability to interact with an object without it explicitly declaring an interface

is known as ‘duck typing’.

We aren’t limited to classes; functions may also be used in this way:

def notify_by_email(customer, event):

...

def notify_by_text_message(customer, event):

...

for notify in (notify_by_email, notify_by_text_message):

notify(customer, event)

We may even use Python modules:

import email

import text_message

for notification_method in (email, text_message):

notification_method.notify(customer, event)

Whether a shared interface is manifested in a formal, object oriented manner, or more implicitly, we can generalise the separation between the interface and the implementation like so:

This separation will give us a lot of power, as we’ll see now.

A second look at the pattern

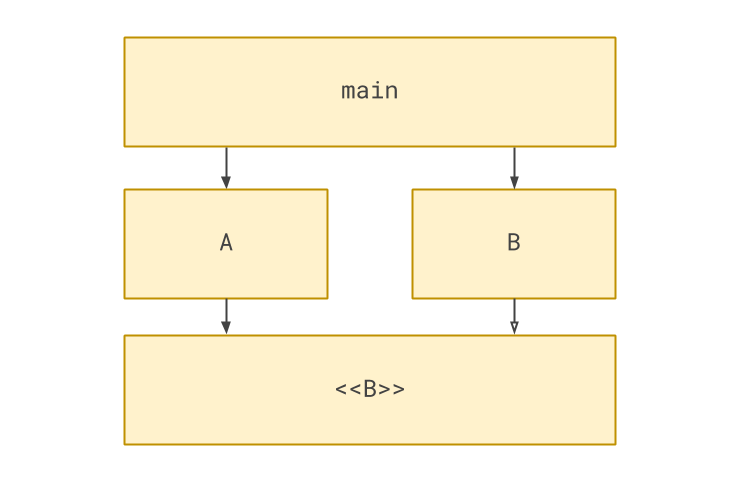

Let’s look again at the Inversion of Control pattern.

In order to invert control between A and B, we’ve added two things to our design.

The first is <<B>>. We’ve separated out into its abstraction (which A will continue to depend on and know about),

from its implementation (of which A is blissfully ignorant).

However, somehow the software will need to make sure that B is used in place of its abstraction. We therefore need

some orchestration code that knows about both A and B, and does the final linking of them together. I’ve called

this main.

It’s now time to look at the techniques we may use for doing this.

Technique One: Dependency Injection

Dependency Injection is where a piece of code allows the calling code to control its dependencies.

Let’s begin with the following function, which doesn’t yet support dependency injection:

# hello_world.py

def hello_world():

print("Hello, world.")

This function is called from a top level function like so:

# main.py

from hello_world import hello_world

if __name__ == "__main__":

hello_world()

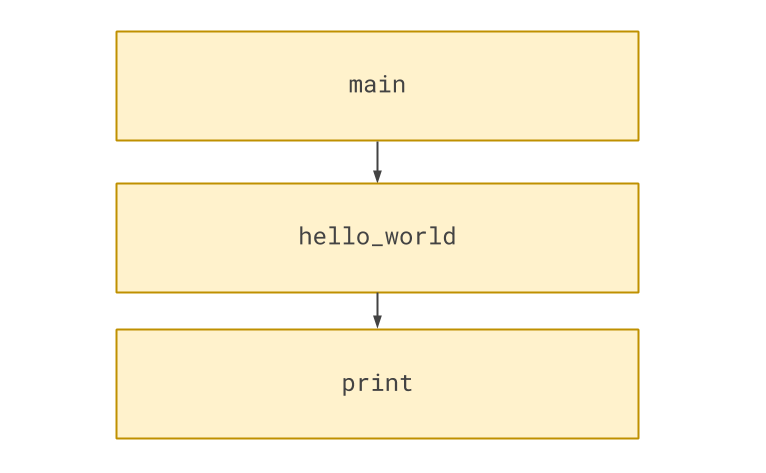

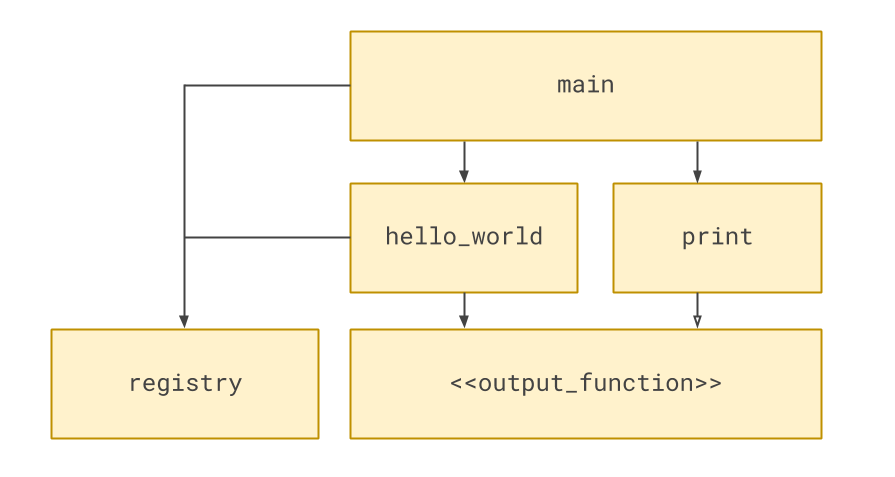

hello_world has one dependency that is of interest to us: the built in function print. We can draw a diagram

of these dependencies like this:

The first step is to identify the abstraction that print implements. We could think of this simply as a

function that outputs a message it is supplied — let’s call it output_function.

Now, we adjust hello_world so it supports the injection of the implementation of output_function. Drum roll please…

# hello_world.py

def hello_world(output_function):

output_function("Hello, world.")

All we do is allow it to receive the output function as an argument. The orchestration code then passes in the print function via the argument:

# main.py

import hello_world

if __name__ == "__main__":

hello_world.hello_world(output_function=print)

That’s it. It couldn’t get much simpler, could it? In this example, we’re injecting a callable, but other implementations could expect a class, an instance or even a module.

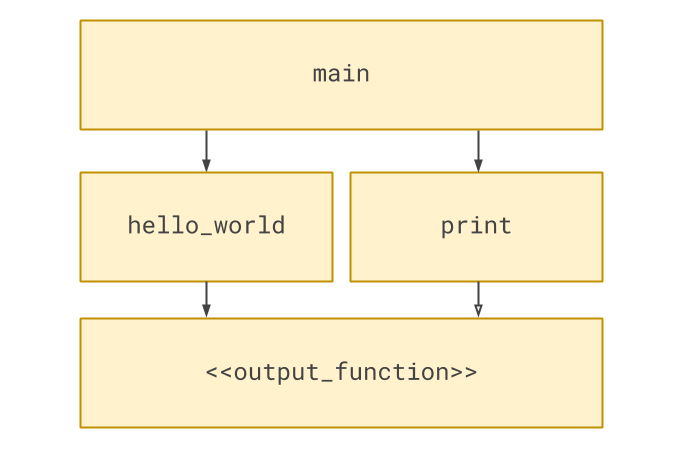

With very little code, we have moved the dependency out of hello_world, into the top level function:

Notice that although there isn’t a formally declared abstract output_function, that concept is implicitly there, so

I’ve included it in the diagram.

Technique Two: Registry

A Registry is a store that one piece of code reads from to decide how to behave, which may be written to by other parts of the system. Registries require a bit more machinery that dependency injection.

They take two forms: Configuration and Subscriber:

The Configuration Registry

A configuration registry gets populated once, and only once. A piece of code uses one to allow its behaviour to be configured from outside.

Although this needs more machinery than dependency injection, it doesn’t need much:

# hello_world.py

config = {}

def hello_world():

output_function = config["OUTPUT_FUNCTION"]

output_function("Hello, world.")

To complete the picture, here’s how it could be configured externally:

# main.py

import hello_world

hello_world.config["OUTPUT_FUNCTION"] = print

if __name__ == "__main__":

hello_world.hello_world()

The machinery in this case is simply a dictionary that is written to from outside the module. In a real world system, we might want a slightly more sophisticated config system (making it immutable for example, is a good idea). But at heart, any key-value store will do.

As with dependency injection, the output function’s implementation has been lifted out, so hello_world no longer depends on it.

The Subscriber Registry

In contrast to a configuration registry, which should only be populated once, a subscriber registry may be populated an arbitrary number of times by different parts of the system.

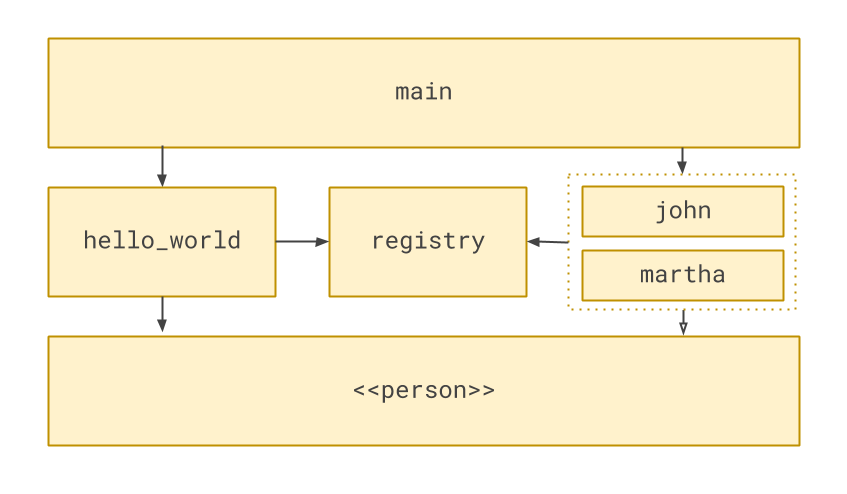

Let’s develop our ultra-trivial example to use this pattern. Instead of saying “Hello, world”, we want to greet an arbitrary number of people: “Hello, John.”, “Hello, Martha.”, etc. Other parts of the system should be able to add people to the list of those we should greet.

# hello_people.py

people = []

def hello_people():

for person in people:

print(f"Hello, {person}.")

# john.py

import hello_people

hello_people.people.append("John")

# martha.py

import hello_people

hello_people.people.append("Martha")

As with the configuration registry, there is a store that can be written to from outside. But instead of being a dictionary, it’s a list. This list is populated, typically at startup, by other components scattered throughout the system. When the time is right, the code works through each item one by one.

A diagram of this system would be:

Notice that in this case, main doesn’t need to know about the registry — instead, it’s the subscribers elsewhere

in the system that write to it.

Subscribing to events

A common reason for using a subscriber registry is to allow other parts of a system to react to events that happen one place, without that place directly calling them. This is often solved by the Observer Pattern, a.k.a. pub/sub.

We may implement this in much the same way as above, except instead of adding strings to a list, we add callables:

# hello_world.py

subscribers = []

def hello_world():

print("Hello, world.")

for subscriber in subscribers:

subscriber()

# log.py

import hello_world

def write_to_log():

...

hello_world.subscribers.append(write_to_log)

Technique Three: Monkey Patching

Our final technique, Monkey Patching, is very different to the others, as it doesn’t use the Inversion of Control pattern described above.

If our hello_world function doesn’t implement any hooks for injecting its output function, we could monkey patch the

built in print function with something different:

# main.py

import hello_world

from print_twice import print_twice

hello_world.print = print_twice

if __name__ == "__main__":

hello_world.hello_world()

Monkey patching takes other forms. You could manipulate to your heart’s content some hapless class defined elsewhere — changing attributes, swapping in other methods, and generally doing whatever you like to it.

Choosing a technique

Given these three techniques, which should you choose, and when?

When to use monkey patching

Code that abuses the Python’s dynamic power can be extremely difficult to understand or maintain. The problem is that if you are reading monkey patched code, you have no clue to tell you that it is being manipulated elsewhere.

Monkey patching should be reserved for desperate times, where you don’t have the ability to change the code you’re patching, and it’s really, truly impractical to do anything else.

Instead of monkey patching, it’s much better to use one of the other inversion of control techniques. These expose an API that formally provides the hooks that other code can use to change behaviour, which is easier to reason about and predict.

A legitimate exception is testing, where you can make use of unittest.mock.patch. This is monkey patching, but it’s

a pragmatic way to manipulate dependencies when testing code. Even then, some people view testing like this as

a code smell.

When to use dependency injection

If your dependencies change at runtime, you’ll need dependency injection. Its alternative, the registry, is best kept immutable. You don’t want to be changing what’s in a registry, except at application start up.

json.dumps is a good example from the standard library which uses

dependency injection. It serializes a Python object to a JSON string, but if the default encoding doesn’t support what

you’re trying to serialize, it allows you to pass in a custom encoder class.

Even if you don’t need dependencies to change, dependency injection is a good technique if you want a really simple way of overriding dependencies, and don’t want the extra machinery of configuration.

However, if you are having to inject the same dependency a lot, you might find your code becomes rather unwieldy and repetitive. This can also happen if you only need the dependency quite deep in the call stack, and are having to pass it around a lot of functions.

When to use registries

Registries are a good choice if the dependency can be fixed at start up time. While you could use dependency injection instead, the registry is a good way to keep configuration separate from the control flow code.

Use a configuration registry when you need something configured to a single value. If there is already a configuration system in place (e.g. if you’re using a framework that has a way of providing global configuration) then there’s even less extra machinery to set up. A good example of this is Django’s ORM, which provides a Python API around different database engines. The ORM does not depend on any one database engine; instead, you configure your project to use a particular database engine via Django’s configuration system.

Use a subscriber registry for pub/sub, or when you depend on an arbitrary number of values. Django signals, which are a pub/sub mechanism, use this pattern. A rather different use case, also from Django, is its admin site. This uses a subscriber registry to allow different database tables to be registered with it, exposing a CRUD interface in the UI.

Configuration registries may be used in place of subscriber registries for configuring, say, a list — if you prefer doing your linking up in single place, rather than scattering it throughout the application.

Conclusion

I hope these examples, which were as simple as I could think of, have shown how easy it is to invert control in Python. While it’s not always the most obvious way to structure things, it can be achieved with very little extra code.

In the real world, you may prefer to employ these techniques with a bit more structure. I often choose classes rather than functions as the swappable dependencies, as they allow you to declare the interface in a more formal way. Dependency injection, too, has more sophisticated implementations, and there are even some third party frameworks available.

There are costs as well as benefits. Locally, code that employs IoC may be harder to understand and debug, so be sure that it is reducing complication overall.

Whichever approaches you take, the important thing to remember is that the relationship of dependencies in a software package is crucial to how easy it will be to understand and change. Following the path of least resistance can result in dependencies being structured in ways that are, in fact, unnecessarily difficult to work with. These techniques give you the power to invert dependencies where appropriate, allowing you to create more maintainable, modular code. Use them wisely!